IN THIS REPORT

- Foreword

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Improving people’s health

and wellbeing - 3. Growing local economies

IN THIS REPORT

Estimating the impact of community business at the neighbourhood level:

Reporting on Kantar Public’s difference-in-difference analysis of the hyperlocal version of the Community Life Survey

November 2023

Chloe Nelson and Rachael Dufour, Power to Change

FOREWORD

By Tim Davies-Pugh

Over the past eight years as a funder, innovator, advocate and champion, we have seen community business in action, and we have built the evidence to show that community business works.

This Community Life Survey Hyperlocal Booster Report exemplifies our renewed commitment to evidencing the impact that community business has, amplifying what works and influencing change to create the conditions for community business to thrive.

It shows, through a new and innovative use of the Community Life Survey, that clusters of community business can create resilience and build personal wellbeing in their local areas in times of crisis. It demonstrates that the Empowering Places programme made places better for the people who live there.

This robust methodology can be replicated by others, to build the body of evidence on what works in place-based funding and community-led development, but more importantly, it offers significant opportunity to inform the way that we work to strengthen communities through community business – from the most local level to the national policy context.

Our place-based Empowering Places programme ran over five years and distributed over £8 million to community catalysts and businesses in Wigan, Leicester, Grimsby, Plymouth, Hartlepool and Bradford. The programme was designed to explore what happens when local anchor organisations are supported to catalyse community businesses in local places. Operating through local community hubs, these catalysts have nurtured, grown, and embedded community business within their local areas.

For example, in Hartlepool, the Wharton Trust has proactively built a cluster of community businesses to meet social prescribing needs, by piloting a combined approach to tackling mental health in the area. The impact of this work is being felt locally and, excitingly, by residents beyond those directly engaged by the community businesses.

The evidence presented in this report shows that when place-based funding is delivered in the right way – in a patient manner, to local organisations equipped with the support and freedom to deliver what matters for their areas – it can create tangible benefits for local people and communities resilient to the challenges ahead of us.

HIGHLIGHT

Power to Change commissioned Kantar Public* to conduct a ‘hyperlocal booster’ version of the Community Life Survey, focused on six places in England participating in our Empowering Places programme. Data was compared using a ‘difference-in-difference’ statistical technique to estimate change over time in the areas we supported, compared with changes seen in similar areas not involved in the programme.

The difference-in-difference analysis found statistically significant positive impacts of the Empowering Places programme between 2018 and 2022 on:

-

- general health in Braunstone (Leicester)

- personal wellbeing in Braunstone (Leicester), Dyke House (Hartlepool) and Nunsthorpe and Bradley Park (Grimsby)

- employment in Abram Ward (Wigan)

- satisfaction with local services and amenities in Nunsthorpe and Bradley Park (Grimsby)

- community pride and empowerment in Devonport and Stonehouse (Plymouth) and Dyke House (Hartlepool)

- civic participation in Braunstone (Leicester)

These impacts are statistically significant ‘net positive increases’ compared with similar areas. They demonstrate that it is likely that community business and catalysts have contributed to positive change in the Empowering Places areas.

The data from the hyperlocal version of the Community Life Survey shows that the Covid-19 pandemic and subsequent economic challenges have had a significant impact on people’s health and wellbeing, employment and volunteering opportunities, as well as their perspectives on their local areas. However, the difference-in-difference analysis shows that residents across all Empowering Places areas experienced greater resilience and less adverse impact on their wellbeing than their comparison areas.

Although the Empowering Places areas mostly saw decreases in wellbeing between 2020 and 2022, this was to a lesser extent than in the comparison areas, which experienced consistent and large decreases between 2018 and 2022. The breadth and strength of the evidence, and the consistency in these trends, means we can reasonably conclude that clusters of community business at a hyperlocal level are likely to have contributed to increasing resilience and wellbeing in the Empowering Places areas in this period

While persistent challenges remain, we know from wider evidence that the Empowering Places programme has had an undeniably life-changing impact on the people that have been involved in the programme. It has helped provide new opportunities in response to community need, offered local jobs and local services through new community businesses, and rebalanced power by putting people at the heart of local decision making.1 Our evidence shows the impact demonstrated through this research can be achieved by:

- Putting local communities in charge

- Flexible and longer-term funding

- Appropriate funding alongside capacity support

- Providing spaces and time for people to connection.

This report demonstrates how long-term investment in community businesses can achieve real and lasting change for local people. However, as impact often takes time to materialise, we may only see the full impact of the Empowering Places programme by monitoring developments in Braunstone, Nunsthorpe and Bradley Park, Abram Ward, Devonport and Stonehouse, Dyke House, and Manningham, over the next five to ten years.

*Following Kantar Public’s divestment from Kantar Group in September 2022, they have now rebranded in all markets where they operate (Europe, APAC and the US), and from November 2023 are to be known as Verian. Due to the timings associated we have mutually agreed to continue to refer to them as ‘Kantar Public’ throughout this report. More information is available in this press release.

FOOTNOTES AND REFERENCES

1 O’Flynn, L., Jones, N., Jackson-Harmon, K., Chan, J. (2023) Five Years of Empowering Places: Evaluation Report, Renaisi/Power to Change, p. 43: https://www.powertochange.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Five-years-of-Empowering-places-Evaluation-report-no.5.pdf

IN THIS REPORT

1 | Introduction

1.1 | BACKGROUND

At Power to Change, we have made significant investments in building the evidence base on the impact of community business on economic, social and environmental wellbeing, and our role in this. Our Empowering Places programme aimed to build more resilient communities by working with locally rooted ‘catalyst’ organisations to develop and nurture community businesses, and to provide benefits and opportunities for local people. In 2018, we wanted to understand whether our long-term investment in the six areas participating in Empowering Places could lead to quantifiable and statistically significant change.

We consequentially commissioned Kantar Public to conduct a ‘hyperlocal booster’ version of the Community Life Survey, an annual survey produced by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport. The evaluation uses a ‘difference-in-difference’ statistical technique, which estimates change over time in the areas in England participating in the Empowering Places programme, compared with changes seen in matched comparison areas (see Chapter 1.3).

Recognising how important it is to draw insights from both quantitative and qualitative evidence, this report shares Kantar Public’s findings, additional data analysis, and learning from the primarily qualitative evaluation of Empowering Places undertaken by Renaisi. This report has been written by Chloe Nelson and Rachael Dufour at Power to Change, with input from Kantar Public and Renaisi.

You can download the full report from Kantar Public and all other source material reports, including the qualitative evaluation from Renaisi, in Chapter 6.

1.2 | EMPOWERING PLACES

Empowering Places was a unique five-year programme delivered from 2017 to 2022, designed by Power to Change to explore ways in which ‘locally rooted’ anchor organisations, operating in areas of high deprivation, could be supported to ‘catalyse’ new community businesses. The programme hypothesised that this, in turn, would contribute to an overarching vision of more prosperous places, with more jobs and opportunities for local people.

The programme provided a blend of funding and capacity-building support to locally rooted ‘catalyst’ organisations in six areas of high deprivation, to develop local networks and grow the sector at neighbourhood level. These catalyst organisations were:

- Wigan and Leigh Community Charity (WLCC), formally Abram Ward Community Cooperative, in Abram, Wigan

- B-inspired in Braunstone, Leicester

- Centre4 in Nunsthorpe and Bradley Park, Grimsby

- Made in Manningham, incubated by Participate in Manningham, Bradford

- Real Ideas in Devonport and Stonehouse, Plymouth

- The Wharton Trust in Dyke House, Hartlepool

Funded by Power to Change, and delivered by Co-operatives UK in partnership with the New Economics Foundation (NEF) and the Centre for Local Economic Strategies (CLES), Empowering Places provided catalyst organisations with a combination of expert guidance from a ‘tech lead’, access to specialist skills and support, grant funding, and money to award seed grants. Each catalyst received up to £1 million (July 2017–2022), and 95 community businesses were supported across the six areas.

1.3 | METHODOLOGY

Since 2012, Kantar Public has carried out the national Community Life Survey (CLS) on behalf of the Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS). This national survey covers topics such as health and wellbeing, employment, and community participation and engagement. It provides an opportunity to capture representative data from the general population on these key topics.

We commissioned Kantar Public to conduct a ‘hyperlocal booster’ version of the Community Life Survey, focused on the six places in England funded through the Empowering Places programme.2 The ‘hyperlocal booster’ survey used the CLS national model and acted as a sample boost for the operational areas where the Empowering Places catalyst organisations operated. This survey, branded as the Neighbourhood Life Survey, contained the same measures, and used identical methods to the CLS for the purposes of difference-in-difference analysis and was conducted in 2018, 2020, and 2022.3 This boosted data collection provides a large enough sample to enable meaningful analysis at a hyperlocal level.

As the CLS is a national survey, Kantar Public can create matched comparison areas from the CLS data set for each operational area.4 This, combined with the multi-wave approach to the research, allows for the use of a statistical method known as ‘difference-in-difference’. This means that we can explore whether there have been changes in the local areas, and whether these changes can reasonably be attributed to the effects of our funding.

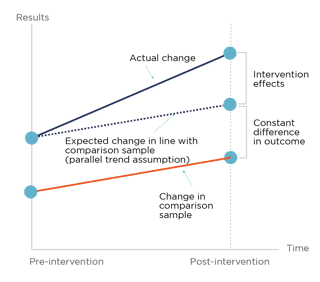

What is difference-in-difference?

Difference-in-difference analysis is a statistical technique that can estimate the effect of an intervention on a specific outcome. It does this by comparing the change in the outcome in the intervention group with change for a control group over the same time period.

In this report, the methodology looks at changes in the local areas participating in the Empowering Places programme, compared with matched comparison samples, and uses difference-in-difference to identify any statistically significant changes. If a change is statistically significant, it means that there is a reasonable chance it is a result of the intervention being evaluated. In this case, that is the Empowering Places programme or the areas in which the catalysts funded through the programme operate (sometimes referred to as ‘catalyst areas’).

In the difference-in-difference chart above, the dark blue line represents the local area participating in the Empowering Places programme. The orange line represents the change in the matched comparison sample for the Empowering Places area, drawn from the national Community Life Survey.

Respondents are not asked about community businesses as part of the ‘hyperlocal booster’ version Community Life Survey and we do not know if they are aware of Power to Change, the Empowering Places programme, the catalyst organisations, or community businesses funded through it. This means that we can understand whether any changes can be seen amongst residents more generally, rather than just those we know have come into direct contact with the community businesses that participated in Empowering Places. This methodology is a robust way of understanding and attributing change:

‘This type of analysis is called ‘difference-in-difference’ and, when combined with sample matching (as here), is one of the most robust impact evaluation methods outside of the randomised controlled trial. To our knowledge, this method has not been successfully implemented elsewhere in the third sector and therefore represents a step forward for evaluation of localised interventions.’ Kantar Public 5

However robust our approach, the measuring, evaluating, and understanding of place-based change remains challenging, especially where primarily quantitative measures are used. We explore these issues further in the next section.

1.4 | LIMITATIONS AND CONSIDERATIONS

Measuring, evaluating, and understanding place-based change can be complex and challenging. It is important, therefore, to treat the findings with some caution:

- Change is not always linear: Change, particularly place-based change, is not necessarily linear, and does not fit into neat patterns that evaluation may require. It is clear from the findings that change fluctuates, but surveys are only conducted at random points in time. Practically, change manifests in complex ways that do not conveniently fit neat timelines for research, or the programmes being evaluated. As this is particularly the case with quantitative approaches, it may still be too early to understand impact over the longer-term, and further fluctuations are possible.

- High threshold for impact: This methodology was delivered to test whether it was possible to see statistically significant quantitative change amongst respondents living in a local area as a result of long-term investment in community businesses in that area, relative to a comparison group. This means that we are looking for evidence of impact amongst those who may have not been directly involved with catalysts or community businesses that have received funding from Power to Change. Additionally, using statistical significance and a comparison group, the methodology imposes a much higher threshold for determining impact than many others commonly used when evaluating place-based change.

- Methodology and context: Kantar Public’s analysis primarily focuses on using difference-in-difference to assess impact and looking at trends within individual outcomes. However, as the survey provides a comprehensive data set that can also be used in multiple other ways, this report includes additional analysis from Power to Change, such as reviewing combined trends over time.

- External factors: A myriad of other factors affect the results of all interventions, but particularly locally-led place-based ones. Notably, the research was carried out in 2018, 2020, and 2022, during which the Covid-19 pandemic had a significant impact, and this is likely to be reflected in the data. Although imperfect, using comparison groups aims to mitigate the risk of distortion, as they are constructed to be similar to the Empowering Places areas.

- Representing disadvantage and marginalisation: The differing experience of the pandemic’s impact, more keenly felt in disadvantaged and marginalised places, also reflects the variety of ways in which any change can be felt and measured. Traditional evaluation methods often favour the majority (for example, by looking for change at a common enough level so as to be considered meaningful and representative), leaving people with experience of discrimination or marginalisation less well served. Although Kantar Public’s approach involved representative samples, accessible, web and paper versions, and incentives for participating in the survey, any quantitative approach will struggle to serve or capture change for everyone, everywhere.

- Expected change: Not all questions within the Community Life Survey map neatly onto the theory of change informing the evaluation of the Empowering Places programme. As a result, we should neither expect to see clear change across all responses (as change was not intended in these areas), nor treat any lack of findings as an absence of impact. As the survey does not capture the entirety of the programme’s impact, a lack of evidence of change does not mean that change is not actually present in those areas.

To supplement our insight in light of these factors, we also invested in a comprehensive qualitative evaluation across the six areas over the same time period, delivered by Renaisi. Focusing on the experiences of those involved in the programme, Renaisi primarily drew from over 100 interviews and video ethnography with catalysts, community businesses, tech leads and stakeholders in the local areas, along with 13 interviews with programme delivery leads at Power to Change and Co-operatives UK. These two complementary approaches help build a more thorough picture of the impact of the programme.

- Methodology and response rate: This report primarily covers findings from the most recent round of research. Fieldwork for the 2022 wave took place between 4 August and 30 September 2022.6 It is standard practice to send two reminders, a fortnight apart, for the Community Life Survey, with a third sent to a targeted subsample of addresses, mainly in deprived areas and/or with a younger household structure. Two paper questionnaires are included in the second reminder for a targeted subset of addresses.7 All respondents who completed the survey received a £10 voucher to thank them for their contribution. The standardised individual response rate achieved in each operational area ranged from 19.5% to 21.8% as shown in Table 1.1.8 As a benchmark comparison, the response rate for the survey in 2020–21 was 22.6%.

| Table 1.1: Response rate by area | |||

| Operational area | Online completions (% of completions) | Paper completions (% of completions) | Total completions |

| Wigan and Leigh Community Charity, in Abram Ward | 272 (76%) | 85 (24%) | 357 |

| B-inspired in Braunstone, Leicester | 254 (64%) | 140 (36%) | 394 |

| Centre4 in Bradley Park, Grimsby | 281 (73%) | 105 (27%) | 386 |

| Real Ideas, in Devonport and Stonehouse, Plymouth | 246 (61%) | 158 (39%) | 404 |

| The Wharton Trust in Dyke House, Hartlepool | 264 (68%) | 127 (32%) | 391 |

- Statistical significance: This difference-in-difference analysis uses a lower rate of statistical significance than ‘standard’ approaches, recognising the complexities involved:

‘The standard significance threshold is usually set at 5%. That means the only observed differences considered ‘statistically significant’ are those that would have a <=5% chance of being observed – due to random sampling error – if there was in fact no difference at the whole population level. However, with small sample sizes (as here), this threshold can lead to the risk of false negatives outweighing the risk of false positives. Consequently, the significance threshold has been shifted upwards: observed differences are considered statistically significant if they would have no more than a one in three (33%) chance of being observed if there was no population-level difference.’

Kantar Public9

- Changed measures: To improve accessibility in the third wave (2022), two of the measures were updated on the web version of the survey. This may have affected the data, and applies to surveys in the Empowering Places areas and the comparison samples:

-

- Limiting long-term illness measure (Zdill/Zpdill). In Wave 1 and Wave 2 the answer code ‘prefer not to say’ was only accessible by clicking the next button without selecting an answer. However, to improve accessibility in Wave 3, this code was readily available for respondents to select as part of the response list on the first page. While this change affected both operational and comparison samples, it is not possible to identify its effect in the data.

- Interest in being more involved in local decision making (ZPCSat). The local decision-making measure was changed in Wave 3. The response ‘it depends on the issue’ was previously only accessible by clicking the next button without selecting an answer. In Wave 3 this option was made readily available to respondents as part of the response list, and there was, consequently, a large increase in the proportion of respondents selecting it in both the operational and comparison samples. As a result, we have not included this data within the report.

- Manningham, Bradford: It was not possible to create a comparison sample from the national Community Life Survey for Manningham in Bradford for the 2022 wave of fieldwork, and budget did not allow a bespoke comparison sample to be constructed instead. Although this third wave did not therefore include a boosted sample for Manningham, relevant difference-in-difference analysis from 2018 and 2020 has been included.

- Limited analysis: Additionally, budget constraints mean that not all responses from all areas have been analysed using difference-in-difference. Instead, Power to Change worked with the local catalyst organisations to provide Kantar Public with a series of hypotheses about their area, informing which sections of the survey were analysed. It is possible, therefore, that there are other changes in the data that have not been reported. However, the full data set has been included within other analysis where relevant or revealing, just not the difference-in-difference. You can download the full data set in Chapter 6.

- Binary variables: Kantar Public used a binary variable approach when conducting the difference-in-difference analysis, using the most appropriate responses to signify change and comparing these with all other responses. Practically, this means grouping together responses such as ‘very high’ and ‘high’ as the data point for analysis.

- Comparison groups: Importantly, the approach uses ‘comparison’ and not ‘control’ groups. This is a quasi-experimental method with a robust approach to analysis. However, it is still an estimated counterfactual, rather than an actual and definitive one.10 As Kantar Public notes:

‘Because the samples from both the two operational areas and their respective comparison groups are imperfect, we urge caution in the interpretation of relative effects11…

To detect impact, the Empowering Places catalyst organisation needs to have a reasonably large effect on its operational area and a relatively close comparison sample has to be identified from within the Community Life Survey national sample. This comparison sample should be large enough to ensure that there is sufficient statistical power to detect unusual effects within the operational area, but not so large that the comparison sample’s similarity to the operational area is lost …

The analysis assumes that controlling for differences in key census statistics and indices of deprivation is enough to eradicate systematic differences between sampled operational areas on the one hand and comparison sample areas on the other.

The comparison sample for each operational area was a subset of respondents in the Community Life Survey 2021–22 who lived in the 10% of English neighbourhoods that are most similar to the operational area.’ Kantar Public12

You can download Kantar Public’s full technical note, which elaborates on the key points made here, in Chapter 6.

-

Empowering Places

FOOTNOTES AND REFERENCES

2It was not possible to create a comparison sample from the national Community Life Survey for Manningham in Bradford for the 2022 wave of fieldwork, and budget did not allow a bespoke comparison sample to be constructed instead. As a result, while surveys were carried out in 2018 and 2020 in Manningham, the 2022 research does not cover this area.

3Fieldwork was conducted in three waves. Wave 1: 16 May–5 August 2018; Wave 2; 13 July–28 August 2020; Wave 3: 4 August–30 September 2022.

4The Empowering Places areas were surveyed in 2018, 2020, and 2022, with the accompanying comparison sample area surveyed in 2017–18, 2019–20, and 2021–22.

5Ozer, A. L., Williams, J., Fitzpatrick, A. and Thaker, D, (2023) Empowering Places? Measuring the impact of community businesses at neighbourhood level: a difference-in-difference analysis, Kantar Public, p. 8.

6Although the fieldwork was conducted in 2022, Kantar Public was unable to analyse the boosted sample data until the main national data set was archived on the UK Data Service by DCMS in April 2023. Kantar Public began the analysis in May 2023.

7Respondents are not asked about community businesses as part of the Community Life Survey and we do not know if respondents are aware of Power to Change, the Empowering Places programme, or catalysts and the community businesses funded through it.

8The ‘standardised’ response rate assumes that 92% of addresses contain households and those households contain an average of 1.9 people aged 16+. These are based on national surveys. In reality, both these numbers will vary from place to place, hence this is a ‘standardised’ response rate rather than a true response rate.

9Ozer, A. L., Williams, J., Fitzpatrick, A. and Thaker, D, (2023) Empowering Places? Measuring the impact of community businesses at neighbourhood level: a difference-in-difference analysis, Kantar Public, pp. 8-9.

10Counterfactual means ‘expressing what has not happened or is not the case’. In evaluation, using a counterfactual helps to understand what would have happened if the intervention or investment being evaluated had not been in place. This approach uses comparison groups to do this but, as the investment has been made, it can only ever be estimated rather than precise.

11The samples for all operational areas are subject to standard limitations of random probability surveying. The matched comparison samples are based on the 10% most similar neighbourhoods.

12Ozer, A. L., Williams, J., Fitzpatrick, A. and Thaker, D, (2023) Empowering Places? Measuring the impact of community businesses at neighbourhood level: a difference-in-difference analysis, Kantar Public, pp. 7-9.

IN THIS REPORT

2 | Improving people’s health and wellbeing

Almost all community businesses (98%) say they have a positive impact on people’s health and wellbeing.13 Evidence shows that people who are using, working, or volunteering for community businesses in the Empowering Places areas are experiencing benefits to their general health and wellbeing.

For example, in Hartlepool, LilyAnne’s Coffee Bar provides ‘socially-prescribed coffees’ to help reduce loneliness and isolation and improve mental health. The community café uses the informality of its space to draw people in and build trust. When they identify people with additional needs, they can refer them to other local community businesses, like mental health support group Minds for Men. In turn, Minds for Men provides training and work placements in the community shop.

Others have a focus on improving people’s physical health, such as Runfit, also in Hartlepool, which is a non-competitive running group accessible to everyone, regardless of ability. ER Crew in Leicester is a community-funded and volunteer run street dance and fitness group, helping children and young people to stay active and healthy.

There is encouraging evidence from the hyperlocal booster version of the Community Life Survey to suggest that the impact of these community businesses on local people’s health and wellbeing is beginning to emerge within the areas in which the catalysts operate. From Kantar Public’s difference-in-difference analysis, it appears that personal wellbeing is the area where the strongest positive evidence emerges across the programme.

Community as remedy: How B Inspired tackles health and social care

2.1 | PERSONAL WELLBEING

The data from the Hyperlocal Booster Community Life Survey shows that there are statistically significant positive trends in the proportion of residents reporting high life satisfaction, fulfilment, and happiness in both Braunstone (Leicester) and Bradley Park (Grimsby), against their comparison groups.14

| Table 2.1: Proportion of residents reporting high personal wellbeing in Braunstone, Leicester | |||||||

| 2018 | 2020 | 2022 | DID | ||||

| CB | MCS | CB | MCS | CB | MCS | ||

| Life satisfaction | 57.2% | 65.9% | 50.4% | 62.4% | 55.6% | 57.1% | 7.1% |

| Happiness | 56.0% | 62.9% | 58.3% | 62.0% | 58.1% | 58.5% | 6.4% |

| Fulfilment | 60.8% | 68.8% | 58.4% | 65.6% | 58.9% | 60.6% | 6.3% |

Abbreviations used in all tables:

- CB = local areas with clusters of community businesses and catalysts participating in Power to Change’s Empowering Places programme

- MCS = matched comparison sample

- DID = difference-in-difference result

- Italicised results = statistically significant

| Table 2.2: Proportion of residents reporting high personal wellbeing in Bradley Park, Grimsby | |||||||

| 2018 | 2020 | 2022 | DID | ||||

| CB | MCS | CB | MCS | CB | MCS | ||

| Life satisfaction | 53.6% | 66.8% | 57.9% | 59.3% | 54.8% | 53.8% | 14.1% |

| Happiness | 58.0% | 63.6% | 57.8% | 60.2% | 56.5% | 55.0% | 7.1% |

| Fulfilment | 55.9% | 68.2% | 62.4% | 64.6% | 58.2% | 58.5% | 12.0% |

Data for both areas shows that the comparison groups started from a much higher position, with wellbeing showing a sustained decrease since 2018. In comparison, wellbeing in the two Empowering Places areas stayed largely consistent during the same time period (see Figures 2.1 and 2.2). This accounts for the positive difference-in-difference findings.

The difference-in-difference analysis for both areas shows that there are statistically significant positive findings across all three of these measures. In addition to the positive findings for life satisfaction, happiness, and fulfilment in Braunstone, Leicester, there were also statistically significant impact on anxiety levels. The proportion of Braunstone residents reporting low anxiety remained relatively consistent (49.3% to 50.2% between 2018 and 2022), whilst the comparison area levels of low anxiety decreased (whilst high levels of anxiety increased). The difference-in-difference estimates that there was a 5.9 percentage point (pp) relative increase in the proportion of Braunstone residents reporting low anxiety, relative to the comparison area.

| Table 2.3: Proportion of residents reporting low anxiety in Braunstone, Leicester | |||||||

| 2018 | 2020 | 2022 | DID | ||||

| CB | MCS | CB | MCS | CB | MCS | ||

| Low anxiety | 49.3% | 52.4% | 50.5% | 50.4% | 50.2% | 47.3% | 5.9% |

These positive findings in Braunstone and Bradley Park are likely to be the result of the work of the Empowering Places catalysts, who use and improve the skills, capabilities, connections, and spaces within their local areas to benefit local people’s wellbeing. Centre4 in Bradley Park, Grimsby has supported several community businesses who support local people with their mental health and wellbeing. This includes Nunny’s Farm, which provides employment and learning opportunities that enable local people to work in nature. With a particular focus on encouraging young people with behavioural difficulties and disabilities to volunteer and interact with animals, it also provides space for local families and individuals to gather. These activities increase wellbeing, create connections, and reduce social isolation.

‘Bringing these community businesses to fruition, it really does make a massive impact, because it’s really having an impact on people’s mental health. The fact that people are able to come to a group, and otherwise they’ll just be isolated at home, or they’ll be lonely or they wouldn’t have that opportunity.’ Catalyst15

There were also positive trends across these measures in Abram Ward (Wigan), but these were not found to be statistically significant. Table 2.4 shows that, personal wellbeing consistently fell between 2018 and 2022. However, wellbeing fell at a greater rate in the comparison sample, which is why the analysis finds ‘positive trends’. This means that although wellbeing has declined in similar areas, the presence of the Empowering Places programme in Abram Ward may have slowed the decline in this area. This is backed up by a positive difference-in-difference finding (1.9pp increase) in relation to those stating that they had low anxiety, although this finding is not statistically significant.

| Table 2.4: Proportion of residents reporting high personal wellbeing in Abram Ward, Wigan | |||||||

| 2018 | 2020 | 2022 | DID | ||||

| CB | MCS | CB | MCS | CB | MCS | ||

| Life satisfaction | 65.8% | 69.7% | 58.6% | 62.7% | 53.5% | 56.8% | 0.5% |

| Happiness | 63.3% | 68.4% | 61.5% | 64.4% | 55.4% | 58.3% | 2.2% |

| Fulfilment | 70.0% | 72.0% | 61.7% | 67.3% | 60.4% | 60.5% | 1.9% |

| Low anxiety | 57.5% | 58.0% | 44.3% | 51.9% | 48.7% | 47.2% | 1.9% |

In Dyke House, Hartlepool, there were statistically significant positive findings in relation to anxiety. Although the proportion who said they had ‘low’ or ‘very low’ anxiety stayed relatively consistent in the area, there was a large drop in the matched comparison sample, which leads to a relative increase of 7.6pp. This suggests that the catalyst and community businesses they supported enabled people to maintain greater resilience during this time.

| Table 2.5: Proportion of residents reporting low anxiety in Dyke House, Hartlepool | |||||||

| 2018 | 2020 | 2022 | DID | ||||

| CB | MCS | CB | MCS | CB | MCS | ||

| Low anxiety | 46.2% | 53.6% | 47.8% | 51.4% | 45.4% | 45.2% | 7.6% |

There were positive trends in other measures of personal wellbeing (life satisfaction, happiness, and fulfilment) in Dyke House. Although these figures saw decreases between 2018 and 2022, their matched comparison samples saw decreases to a greater extent. There are clear trends in this data, which show that wellbeing consistently increased in the catalyst areas between 2018 and 2020, indicating emerging positive impact, before dropping dramatically in 2022. In contrast, the matched comparison area saw consistent decreases between 2018, 2020, and 2022:

| Table 2.6: Proportion of residents reporting high personal wellbeing in Dyke House, Hartlepool | |||||||

| 2018 | 2020 | 2022 | DID | ||||

| CB | MCS | CB | MCS | CB | MCS | ||

| Life satisfaction | 57.0% | 67.2% | 62.6% | 58.8% | 47.9% | 53.9% | 4.2% |

| Happiness | 59.1% | 63.2% | 64.1% | 59.6% | 52.6% | 56.2% | 0.5% |

| Fulfilment | 61.3% | 67.2% | 65.0% | 63.8% | 55.1% | 58.9% | 2.1% |

While these three measures are not statistically significant, the overall trends in Dyke House are broadly positive, and indicate a maintenance in multiple measures of wellbeing. The positive trends are consistent with the patterns seen in Braunstone, Bradley Park, and Abram Ward; overall wellbeing has fallen, but it has not fallen as much in the areas in which catalysts operate.

Personal wellbeing decreased in Devonport and Stonehouse (Plymouth), but again, there were no statistically significant trends compared with the matched comparison sample. While Renaisi’s evaluation indicates how direct contact with the programme can have a strong impact on wellbeing – for example, Pillars of Wellness provides accessible information on wellness and wellbeing and runs low-cost or free events for the local community in Devonport – it may be too soon, or not widespread enough, to have an impact at a general population level.

The Community Life Survey also asks residents about their social support networks and feelings of loneliness. Only two areas were tested for these social isolation metrics – Nunsthorpe and Bradley Park (Grimsby) and Devonport and Stonehouse (Plymouth). The only statistically significant trend was a 4.8pp relative decrease in the proportion of Nunsthorpe and Bradley Park residents who reported that they have someone they can count on to listen.

| Table 2.7: Proportion of residents agreeing there is at least one person they can really count on to listen to them in Nunsthorpe and Bradley Park, Grimsby | |||||||

| 2018 | 2020 | 2022 | DID | ||||

| CB | MCS | CB | MCS | CB | MCS | ||

| Count on to listen | 92.5% | 91.1% | 94.6% | 95.7% | 91.5% | 94.8% | -4.8% |

Despite this finding, there is strong evidence to indicate that the efforts of the catalysts and the cumulative impacts of the community businesses they have supported have enabled communities to maintain better personal wellbeing during a time in which this was severely affected across the country by the Covid-19 pandemic and its aftermath. Matched comparison samples saw consistently negative trends across measures of wellbeing between 2018 and 2022. In contrast, Empowering Places areas mostly saw increases between 2018 and 2020, before decreasing in 2022, but to a lesser extent than in the comparison areas. In some areas, these positive differences were statistically significant across multiple measures of wellbeing. Other areas saw statistically significant positive findings in one measure, and positive trends in others. The breadth and strength of the evidence and consistency in these trends means we can reasonably assume that the catalysts are likely to have contributed to increased resilience and maintained wellbeing during this challenging time.

2.2 | General health

Personal wellbeing is inextricably linked with overall health, and many community businesses building wellbeing also support people’s physical health through creating accessible and equitable spaces and groups for beneficial activities, such as exercise or growing food. Wigan Cosmos Football Club, for example, took ownership of St John’s Street Playing Fields in their local area through a community asset transfer, from which they offer a wide range of inclusive competitive and social sports opportunities, to build skills, fitness, and wellbeing.

Around 9% of community businesses in England provide direct health and social care services to their community.16 For example, Hartlepool Ambulance Charity, supported by The Wharton Trust, works in partnership with the community to improve quality of life through medical education, enhancing the health and wellbeing of local people, and fundraising jointly to help save local lives.

People’s health was severely affected during the pandemic, and evidence shows that deprived communities and minoritised ethnicity groups were disproportionately affected and are at greater risk of ill health.17 As the Empowering Places programme serves areas of high deprivation, we would expect to see this reflected in the data. Since 2018, self-reported ‘good’ general health has seen small declines in all areas, except Braunstone.18 These trends were not found to be statistically significant in the difference-in-difference analysis. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the majority saw a small increase between 2018–2020, indicating that health was improving before it fell in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Braunstone, in Leicester, showed a statistically significant positive trend in general health, where the proportion of residents who rated their health as ‘fair’, ‘good’ or ‘very good’ increased from 89.1% to 91.2% (4.6pp relative increase). This means that the catalyst organisation funded through Empowering Places may have contributed to people’s improvements in general health during this time.

| Table 2.8: Proportion of residents reporting good general health in Braunstone, Leicester | |||||||

| 2018 | 2020 | 2022 | DID | ||||

| CB | MCS | CB | MCS | CB | MCS | ||

| General health | 89.1% | 90.7% | 90.5% | 95.0% | 91.2% | 88.7% | 4.1% |

The Hyperlocal Booster Community Life Survey asked people whether they have limiting long-term illnesses and health issues, which yielded mixed findings. With the exception of Devonport and Stonehouse, Figure 2.10 shows that limiting long-term illness saw very small changes between 2018 and 2020, before increasing in 2022.

Just one area (Dyke House) saw a statistically significant change relative to its comparison sample. As long-term illness was not an area of expected or intended impact for the programme, we remain cautious of drawing any conclusions about the programme’s impact on this indicator amongst residents living in the catalyst areas.19 However, the data offers interesting findings beyond the difference-in-difference analysis, with consistent increases in limiting long-term illness likely resulting from the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, aligning with other health and wellbeing data.

Overall, and considering both general trends and the difference-in-difference analysis, health and wellbeing findings show some clear positive impacts on personal wellbeing emerging amongst those who live in the areas surrounding local catalysts. There is strong evidence that residents across all Empowering Places areas enjoyed greater resilience and experienced less negative impact on their wellbeing as a result of the pandemic and its subsequent impacts, when viewed against their comparison areas. This change can be reasonably attributed to the work of the catalysts and community businesses funded through the Empowering Places. This evidence suggests that expanding long-term investment in place-based locally rooted catalyst organisations has the potential to yield significant social and economic benefits, cost savings in relation to the use of mental health services and economic inactivity, as research shows that mental health problems cost the UK economy at least £117.9 billion each year, equivalent to around 5% of UK’s GDP.20

It is little surprise that, while the impact on general health and limiting long-term illness is less clear, the trends in findings and insight from the areas themselves show that the pandemic has had a notable impact on people’s health and wellbeing. This inevitably makes it hard for the Empowering Places programme to demonstrate clear and consistent increases over the time period – the positive impact is instead as a result of its ability to maintain wellbeing during an incredibly challenging time, in contrast to matched comparison areas.

Chapter 3 explores the impact of Empowering Places on employment, skills, and volunteering.

FOOTNOTES AND REFERENCES

13Power to Change and CFE Research (2022) Community Business Market Report 2022, Section 3: https://www.powertochange.org.uk/evidence-and-ideas/market-report-2022/better-places/#3-0

14Significant positive trends in wellbeing measures include high and very responses to the questions: “How satisfied are you with your life as a whole nowadays?” (Life satisfaction), “How happy did you feel yesterday” (Happiness) and “To what extent do you feel like things in your life are worthwhile?” (Fulfilment).

15O’Flynn, L., Jones, N., Jackson-Harmon, K., Chan, J. (2023) Five Years of Empowering Places: Evaluation Report, Renaisi/Power to Change, p. 27: https://www.powertochange.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Five-years-of-Empowering-places-Evaluation-report-no.5.pdf

16Power to Change and CFE Research (2022) Community Business Market Report 2022: www.powertochange.org.uk/market-reports/market-report-2022/

17Office for National Statistics (2020) Why have Black and South Asian people been hit hardest by Covid-19?: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/articles/whyhaveblackandsouthasianpeoplebeenhithardestbycovid19/2020-12-14

18As this question was only asked in the web-based version of the survey, it has a slightly lower response rate.

19O’Flynn, L., Jones, N., Jackson-Harmon, K., Chan, J. (2023) Five Years of Empowering Places: Evaluation Report, Renaisi/Power to Change, p. 7: https://www.powertochange.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Five-years-of-Empowering-places-Evaluation-report-no.5.pdf

20McDaid, D., Park, A-L., et al. (2022) The economic case for investing in the prevention of mental health conditions in the UK, Mental Health Foundation and London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE): https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/sites/default/files/2022-06/MHF-Investing-in-Prevention-Full-Report.pdf

3 | Growing local economies

Community businesses play a vital role in their local economies through providing jobs, selling goods and services, and trading in response to local needs. Evidence shows that, compared with the private sector, a higher proportion of what they spend stays in their local community, and their trading income is invested in developing and delivering more services and facilities for local people.21

The Empowering Places programme enabled the local catalyst organisations to seed and support 95 community businesses through incubation, championing individual entrepreneurialism, and being community-led. Around two-thirds of these community businesses remained operational at the end of the programme.22 23 From the survey of more than 1,000 community businesses, our most recent Community Business Market Report (2022) indicates that the average community business has an estimated annual trading income of around £34,000, meaning that the 64 community businesses from Empowering Places could collectively generate around £2.2 million a year in revenue from trading in their local areas.

In many of the places, the catalysts funded through the programme have supported the transfer of local assets into community hands, which enable community businesses to trade and deliver vital services and improve social infrastructure by providing more spaces for the community to come together. For example, Empowering Places enabled B-inspired in Leicester to take on stewardship of The Grove, an unused council building transformed into a vibrant community hub. These activities provide volunteering opportunities, skills growth, employment, and generate financial and economic benefits for local areas.

3.1 | EMPLOYMENT

Our Community Business Market survey data shows that each community business employs an average of nine paid staff, with the majority living locally. This means that the community businesses supported by the Empowering Places catalysts are likely to provide employment to almost 500 paid staff from their local communities.24 45% of these community businesses are likely to have employed someone who was formerly unemployed in the last year. For some community businesses supported through the programme, providing local and meaningful employment is at the heart of their mission. For example, the Ethical Recruitment Agency (ERA) in Grimsby helps local people develop the skills required to access employment opportunities, and works with businesses to place them in work. ERA has been highly successful, taken on several contracts and placed more than 108 people in permanent jobs, the majority of which were full-time, as well as an additional 180 into temporary work on their payroll. While not all of these jobs can be directly attributed to Empowering Places, some can. In Plymouth, the catalyst Real Ideas has identified around 20 paid employment opportunities as a result of the programme.

However, the extent to which this translates into improved employment opportunities in the six local areas, in areas of high deprivation facing persistent challenges, is unclear. It may well be too soon to be apparent – particularly given that areas are still recovering from the impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic and suffering from the current cost-of-living crisis – or interventions may not be large enough to have had an impact on those not directly involved in the programme yet.

Data from the ‘hyperlocal booster’ version of the Community Life Survey shows that, on the whole, self-reported employment has fallen between 2018 and 2022 in both the Empowering Places areas and their matched comparisons. This is in line with national trends indicating that employment in 2022 was still below pre-pandemic levels.25

In 2022, levels of self-reported employment were lower in all catalyst areas compared with their matched comparison samples, but the catalyst areas also started from a lower point in 2018. This is an interesting finding, showing that the areas funded through the programme are likely to have lower levels of employment than their matched comparisons, despite other similar characteristics. This is indicative of the persistent levels of need in these places.

There were positive statistically significant employment trends in Abram Ward in Wigan, where self-reported employment increased 9.6pp relative to the comparison sample. The data shows that the positive impact is driven by a notable decrease in employment in the comparison sample, while employment stayed stable in Abram Ward over the same time period.

This may indicate that Abram Ward has demonstrated more resilience to external economic shocks as a result of the programme and local community businesses, in contrast with the comparison group.

‘It is possible that employment programmes like [Wigan and Leigh Community Charity] have had a positive impact [on this finding]. There is also a possibility of a floor effect under which employment in Abram Ward would typically not decrease unless the area experienced a highly extreme economic downtown. Alternatively, there could be external forces that impact the comparison group that are simply not present in Abram Ward. While it is difficult to ascertain with certainty which of these scenarios is the case, the data nonetheless shows the negative forces impacting similar areas have not impacted Abram to the same degree.’

-Kantar Public

These conditions could also apply where the inverse is true; employment has fallen in two areas at a greater rate than in their matched comparison samples. Nunsthorpe and Bradley Park (10.1pp relative decrease) and Devonport and Stonehouse (7.4pp relative decrease) both saw statistically significant decreases in self-reported employment. This was driven by falls in both the comparison and catalyst areas, but the rate of decline was greater in the catalyst areas. This could mean that the catalyst areas have been affected by external economic shocks to a greater extent than their comparison areas, or by different conditions that are not present in the comparison samples. There were no other statistically significant findings related to employment, and the mixed findings in this area make it difficult to determine a clear pattern.

| Table 3.1: Proportion of residents in employment | |||||||

| 2018 | 2020 | 2022 | DID | ||||

| CB | MCS | CB | MCS | CB | MCS | ||

| Abram Ward, Wigan | 55.1% | 68.5% | 55.9% | 65.2% | 55.5% | 59.4% | 9.6% |

| Braunstone, Leicester | 57.6% | 66.7% | 55.8% | 55.7% | 50.8% | 58.8% | N/A |

| Nunsthorpe and Bradley Park, Grimsby | 59.3% | 60.3% | 49.8% | 55.6% | 45.7% | 56.9% | -10.1% |

| Devonport and Stonehouse, Plymouth | 61.0% | 62.4% | 57.5% | 60.7% | 50.0% | 58.8% | -7.4% |

| Dyke House, Hartlepool | 57.6% | 66.7% | 55.8% | 55.7% | 50.8% | 58.8% | -6.7% |

Although the survey was not carried out in 2022 in Manningham, Bradford, data from previous waves shows that there was a statistically significant decrease in the proportion of people reporting that they were unemployed between 2018 and 2020, compared with the comparison sample. This corresponded with a decrease in those in employment in the comparison area, but this was not statistically significant.

| Table 3.2: Proportion of residents in employment in Manningham, Bradford | |||||

| 2018 | 2020 | DID | |||

| CB | MCS | CB | MCS | ||

| In employment | 41.5% | 54.7% | 42.0% | 49.5% | 5.5% |

| Unemployed | 8.3% | 4.4% | 4.1% | 7.6% | -7.4% |

| Economically inactive | 50.1% | 41.0% | 53.9% | 42.8% | 1.9% |

While some positive findings on employment and enterprise are emerging in the Empowering Places areas, they are on the whole mixed. Employment levels are, perhaps, more likely to be affected by wider economic challenges, than interventions by local catalysts and community businesses. It also may be that broader change does not materialise for many years, by which point it becomes harder to determine attribution. Empowering Places was designed to seed new community businesses, and this meant, in many cases, starting with a ‘person with an idea’. At the end of the Empowering Places programme in 2023, only an estimated 40% of community businesses were in the growth or scale stage of their life cycle; the stages where broader impact typically tends to materialise.26 It may be a while until these community businesses supported by Empowering Places realise their full potential and impact is felt on the community.

For example, the catalysts in both Wigan and Grimsby are using schools’ enterprise programmes to connect with young people and support their thinking about different career options, including social enterprise. This has ‘lifted the profile of social businesses to young people who are unemployed’.27 Similarly, the Millan Centre in Manningham (Bradford), provides classes for women who haven’t had the opportunity or confidence to learn English before. In response to local demand, the centre also offers qualifications in health and wellbeing, and hairdressing and beauty, which could lead to positive impacts in this area in future:

‘I’ve come here to learn English because I need it for my little one, she’s starting school and I, I really want to help her … And maybe more learning is good for me in the future, to find work.’ Millan Centre beneficiary

3.2 | VOLUNTEERING

Volunteers play an essential role in running community businesses. They sit on boards and committees, deliver services, work in cafés, shops and other trading operations, provide administrative and back-office support, and support local people. The Empowering Places catalysts and the community businesses they have supported provide a multitude of volunteering opportunities in their local areas. For example, in Grimsby, a resident volunteered to run the community gym, and in Leicester, the community bar is being run by a group of local people with experience in hospitality. Although overall volunteering numbers have fallen since the Covid-19 pandemic, it is estimated that there are still 126,000 people volunteering in community businesses in England.28 This translates to almost 900 volunteers within the community businesses in the Empowering Places areas, 92% of whom are likely to live locally.29

Volunteering benefits community businesses, local people, and those undertaking the roles; reducing social isolation, improving wellbeing, building skills and personal achievement.30 It also provides an important route to paid work, with many volunteers in community businesses moving into employment either with or outside the organisation. For example:

‘Two of the girls that are coming today started off as participants, and then became junior coaches. So, they came on board as staff, and we qualified them. They did an apprenticeship with us, and now they’ve been working with us for the last four years.’ Community business staff member

These positive impacts were evident for those volunteering with community businesses and catalysts participating in Empowering Places programme:

‘In some cases, volunteers have improved their knowledge, skills and confidence to a point where they have either been taken on as staff by the community business or have found work elsewhere:

'It gave me the confidence to get back into work and then go in from a volunteer to paid hours and now I have, you know, a secure job, so to speak, what’s local and I’m giving back.' Volunteer

Through developing knowledge and skills, catalysts and community businesses have therefore grown the resources available to them, with each place developing an ever increasing pool of volunteers who not only want to support their community but who are also increasingly understanding the value of community business.’ Renaisi31

Despite strong impacts on volunteering for those directly involved with the Empowering Places programme, this has not yet had an impact on wider volunteering levels in the catalyst areas. The Community Life Survey asks residents whether they engage in formal and informal volunteering, and the frequency of their participation. Formal volunteering refers to giving unpaid help to groups or clubs, whilst informal volunteering is defined as giving unpaid help to individuals who are not a relative. The results from the hyperlocal version of the Community Life Survey show that numbers of volunteers have dropped across all measures of volunteering, in all areas, as well as within their comparison samples. For example, Figure 3.6 shows that the proportion of monthly formal volunteering has dropped across all Empowering Places areas.

This is not surprising, considering volunteering levels have largely decreased across the country since the Covid-19 pandemic. In 2021/22, national participation rates for monthly formal volunteering across the country are the lowest since the Community Life Survey started collecting data (16%, approximately 7 million people in England).32 A recent report by Durham University on trends within community businesses similarly found that half (53%) of community businesses are finding it harder to hold onto regular volunteers, and about a third (35%) are losing volunteers who joined them during the pandemic. These challenges with volunteer retention were seen across all other third sector organisations.33

These patterns consistently arise within the data from the Hyperlocal Booster Community Life Survey. For example, the analysis in Abram Ward, Wigan shows that volunteering, both formal and informal, mostly either increased or stayed consistent between 2018 and 2020, before dropping across Abram Ward and the comparison sample in 2022. The difference-in-difference analysis of this data did not find the changes to be statistically significant.

There were three statistically significant negative trends showing that volunteering has fallen in the Empowering Places areas against to their comparison groups. Interestingly, all three areas started with higher numbers of volunteers than their matched comparison samples. This may indicate that our areas have felt disproportionately large effects of the pandemic on volunteer numbers. Formal regular volunteering in Dyke House saw a relative decrease of 4.9pp compared with its comparison sample.

| Table 3.3: Proportion of residents engaging in formal volunteering at least once a month | |||||||

| 2018 | 2020 | 2022 | DID | ||||

| CB | MCS | CB | MCS | CB | MCS | ||

| Dyke House, Hartlepool | 14.6% | 13.2% | 10.3% | 11.9% | 7.7% | 11.2% | -4.9% |

There was also a 5.6pp relative decrease in Braunstone, and a 9.8pp relative decrease in Dyke House for those engaging in informal help at least once a month.

| Table 3.4: Proportion of residents engaging in informal help at least once a month | |||||||

| 2018 | 2020 | 2022 | DID | ||||

| MCS | MCS | MCS | |||||

| Braunstone, Leicester | 27.8% | 23.5% | 26.3% | 29.5% | 23.1% | 24.3% | -5.6% |

| Dyke House, Hartlepool | 29.7% | 22.7% | 33.1% | 30.2% | 21.5% | 24.3% | -9.8% |

Although Manningham, Bradford, was not surveyed in 2022, the difference-in-difference analysis for the area from 2020 backs up this trend, where there were statistically significant positive findings on providing informal help both once a month (20.3pp relative increase) and in the last 12 months (14.8pp relative increase).

Despite strong impacts on those who volunteer within the catalysts and community businesses supported through the Empowering Places programme, the Covid-19 pandemic has evidently had a big impact on the numbers and frequency of volunteering across the country. While the pandemic led to an initial spike in volunteering as communities worked together to deliver food, medicines, and vaccines, with community businesses at the heart of much of this community organising, over the longer term the number of opportunities have reduced.35 Community businesses share that volunteers have needed to seek paid work opportunities due to the cost-of-living crisis, or because their health is declining. Unfortunately, this is reflected in the data in both the catalyst areas and their comparison samples and has arguably affected the extent to which this outcome is likely to materialise within the Hyperlocal Booster Community Life Survey results. It is possible, therefore, that the fall in volunteering levels seen in the data could be attributed to the wider impacts of the pandemic on volunteering within community businesses.

Chapter 4 looks at the data on local environment, community cohesion, and social action.

FOOTNOTES AND REFERENCES

21Power to Change and CFE Research (2022) Community Business Market Report 2022: www.powertochange.org.uk/market-reports/market-report-2022/

22Of these 95, 64 are operational at the time of writing (October 2023).

23O’Flynn, L., Jones, N., Jackson-Harmon, K., Chan, J. (2023) Five Years of Empowering Places: Evaluation Report, Renaisi/Power to Change: https://www.powertochange.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Five-years-of-Empowering-places-Evaluation-report-no.5.pdf

24Power to Change and CFE Research (2022) Community Business Market Report 2022: www.powertochange.org.uk/market-reports/market-report-2022/

25House of Commons Library (2022) Coronavirus: Impact on the labour market, research briefing, 9 August 2022: https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-8898/CBP-8898.pdf

26O’Flynn, L., Jones, N., Jackson-Harmon, K., Chan, J. (2023) Five Years of Empowering Places: Evaluation Report, Renaisi/Power to Change, p. 34: https://www.powertochange.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Five-years-of-Empowering-places-Evaluation-report-no.5.pdf

27O’Flynn, L., Jones. N., and Jackson-Harman, K. (2022) Empowering Places: Impact on the Community and Wider Place, Renaisi/Power to Change, p.11: https://eprints.icstudies.org.uk/id/eprint/408/1/PTC_3833_Empowering%20Places_Report_FINAL.pdf

28Power to Change and CFE Research (2022) Community Business Market Report 2022: www.powertochange.org.uk/market-reports/market-report-2022/

29Power to Change and CFE Research (2022) Community Business Market Report 2022: www.powertochange.org.uk/market-reports/market-report-2022/

30Higton, J., Archer, R., Merrett, D., Hansel, M., and Spong, S. (2021) The role of volunteers in community businesses, CFE Research/Power to Change: https://www.powertochange.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/PTC_CFE_Volunteers_Report_V2.pdf

31O’Flynn, L., Jones, N., Jackson-Harmon, K., Chan, J. (2023) Five Years of Empowering Places: Evaluation Report, Renaisi/Power to Change, p. 24: https://www.powertochange.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Five-years-of-Empowering-places-Evaluation-report-no.5.pdf

32Department for Culture, Media and Sport (2023) Community Life Survey 2021/22: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/community-life-survey-202122

33Chapman, T. (2023) Community Businesses in England and Wales 2022: New findings from Third Sector Trends, Durham University/Power to Change: https://www.powertochange.org.uk/evidence-and-ideas/research-and-reports/community-business-in-england-and-wales-new-findings-from-third-sector-trends/

34Higton, J., et al. (2021), The Community Business Market in 2021, CFE Research: https://www.powertochange.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Community-Business-Market-in-2021-Report.pdf

4 | Enhancing local spaces

Community business can improve local places by providing more spaces for the community to come together. In our 2022 Community Business Market Survey, 98% of community businesses said they had a positive impact on community cohesion. Community businesses can also play a vital role in community-led regeneration, helping recover local infrastructure and high streets. It is estimated that the total value of assets owned by the community business sector is £744 million and that 9% of community businesses have taken ownership of a new asset in the past year.35

There is strong evidence that the catalysts supported through the Empowering Places programme, such as Centre 4 in Grimsby, have revitalised community hubs to deliver key services and activities to the community:

‘What lends itself really uniquely with Centre4 is the fact that this centre is situated at the heart of a housing estate … it used to be an old school … you’ve got rooms … you’ve got a big main hall, you’ve got the sports facilities, or you’ve got this field, and then obviously, you have the area where the farm is … it’s got all these different spaces to then be things that are on offer for the community to support them with a host of different services.’ Catalyst

The Empowering Places programme enabled many community businesses to transform unused or inaccessible spaces into places for the community, improve the reach of their existing community services and spaces, or take new assets into ownership. Community businesses were able to use or unlock local assets for community use, with the help of their local catalyst organisations.

For example, Hub 617 transformed a formerly run-down community space in Platt Bridge, Wigan, into a hub offering a safe space for care-leavers. It provides personal advisors to help care-leavers with training and job hunting, and to ease transition to adulthood. In Braunstone Leicester, community catalysts supported the development of a second-hand shop (Preloved@45 Community Shop) and bar (The Penalty Box Social Bar CIC), neither of which existed in Braunstone prior to the Empowering Places programme. Braunstone residents also commented that the development of a local football club, run by FSD Academy and currently with six active teams, meant their local park is not only more widely used in the evening, but also makes it feel like a nicer and safer place to be for the community as a whole.36 Despite these strong direct impacts, the data reveals the difficulties of demonstrating this impact at a community-wide level, particularly among those who have not been involved directly with the Empowering Places programme.

4.1 | Local environment

Although there is clear evidence of the impact of Empowering Places on individuals and community businesses, it is harder to demonstrate the impact of improved local spaces on the community and wider place at this stage and in the context of recent pervasive challenges. The Community Life Survey asks about people’s satisfaction with their local area as a place to live. When looking at the hyperlocal data, trends show that two areas saw a consistent decline in satisfaction, whilst the other areas increased between 2018 to 2020, before dropping again in 2022.

There were statistically negative trends in three Empowering Places areas: Braunstone, Devonport and Stonehouse, and Dyke House. This is driven by satisfaction levels in the comparison samples increasing (Dyke House) or remaining consistent (Braunstone, Devonport and Stonehouse), while catalyst areas declined.

| Table 4.1: Proportion of residents satisfied with their local area as a place to live | |||||||

| 2018 | 2020 | 2022 | DID | ||||

| CB | MCS | CB | MCS | CB | MCS | ||

| Braunstone, Leicester | 61.1% | 60.7% | 57.6% | 61.8% | 55.1% | 60.9% | -6.2% |

| Devonport and Stonehouse, Plymouth | 74.7% | 67.6% | 78.6% | 72.4% | 68.9% | 67.3% | -5.5% |

| Dyke House, Hartlepool | 57.1% | 58.8% | 55.4% | 65.5% | 52.6% | 61.8% | -7.5% |

Similarly, there were statistically negative trends in Devonport and Stonehouse (12.7pp decrease) and Dyke House (5.3pp decrease) for whether the area has become a better place to live over the past two years.

| Table 4.2: Proportion of residents agreeing area has gotten better to live in over the past two years | |||||||

| 2018 | 2020 | 2022 | DID | ||||

| CB | MCS | CB | MCS | CB | MCS | ||

| Devonport and Stonehouse, Plymouth | 36.9% | 15.4% | 25.4% | 16.5% | 24.5% | 15.7% | -12.7% |

| Dyke House, Hartlepool | 18.5% | 13.8% | 11.8% | 14.9% | 13.1% | 13.8% | -5.3% |

It is unclear what caused these changes, though they are indicative of the persistent challenges that communities are facing. It may also be likely that it is too soon to demonstrate the impact of recent investment. In 2020/21, Plymouth received £16.1 million in grant funding, almost £7 million of which went towards Plymouth’s culture and sport voluntary and community sector organisations.37 There is anecdotal evidence that this funding has improved local infrastructure and supported the local community with asset transfers. For example, licensing park land around Stiltskin Theatre has had a dramatic effect on ticket sales and community engagement, as well as restoring nature:

‘People are travelling to the space ... I know lots of families who will travel to the park for the [Stiltskin] theatre and then will enjoy the rest of the park. It’s that whole thing about breaking down barriers to what Devonport is all about. That whole space, that part of the park where they work now, is much more beautiful. And the fact that they have done festivals and activities there that have made it really beautiful has changed the whole atmosphere of the park.’ Stakeholder38

Plymouth stakeholders have previously indicated that they believed a shift was occurring in the area and that Empowering Places grants and community businesses were part of the change taking place.39

Community businesses create better access to a range of services for their local community. The hyperlocal focus of Empowering Places has meant that catalysts and community businesses have been able to develop opportunities for local people that are engaging and relevant for them. Evidence shows that local people are benefiting from the services and activities that the community businesses are delivering and that, even if people are not directly involved with the community business by using or working with them, the programme has provided a range of opportunities for individuals to engage with the community and share their views.40

When reviewing the trend data from the Hyperlocal Booster Community Life Survey, it appears that most areas saw a small increase in levels of satisfaction with local services between 2018 and 2020, before falling again in 2022. Evidence from our Community Business Market surveys show how community businesses played a vital role in providing services directly to local people during the pandemic, which may be correlated with a spike during the 2020 wave.

There were two contrasting statistically significant difference-in-difference trends in resident satisfaction with local services and amenities from 2018 and 2022 – a 5.8pp comparative increase for Nunsthorpe and Bradley, Grimsby relative to the comparison area, and a 5.8pp decrease in Dyke House, Hartlepool.

| Table 4.3: Proportion of residents satisfied with local services and amenities | |||||||

| 2018 | 2020 | 2022 | DID | ||||

| CB | MCS | CB | MCS | CB | MCS | ||

| Nunsthorpe and Bradley Park, Grimsby | 58.4% | 66.5% | 65.9% | 70.8% | 61.5% | 63.9% | 5.8% |

| Dyke House, Hartlepool | 61.4% | 67.6% | 61.6% | 71.1% | 53.6% | 65.7% | -5.8% |

The positive increase for satisfaction in Grimsby is supported by qualitative insight from Renaisi’s evaluation. Centre4, the catalyst organisation and community hub in Nunsthorpe and Bradley Park, is currently home to a community shop, gym, farm, and recruitment agency in Grimsby and many of these community businesses were set up through the Empowering Places programme. Residents visiting Centre4 would find themselves using multiple services housed in and around the community hub, which could have improved visibility and therefore satisfaction with local services:

‘People will come in for the café and may then use the community library, then they might think “Oh, I need … the advice service” that they offer.’Stakeholder41

In contrast, Dyke House in Hartlepool saw statistically significant negative trends in all three metrics on ‘local environment’ in the Hyperlocal Booster Community Life Survey, including local services and amenities, and perceptions of whether the area is getting better to live in. Hartlepool also has the lowest UK Social Fabric Index score (3.7, compared to a UK median of 4.9) of the six catalysts, suggesting more persistent challenges in this area than the others. This data and insight helps the catalyst decide how best to direct its efforts. For example, The Wharton Trust, the Dyke House catalyst, identified issues with unethical landlords and poor-quality and badly maintained housing, which have been exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic and cost-of-living crisis.42 In response, they set up a new community business, The Annexe Housing Initiative, to provide good quality housing and train local people in the properties to be community organisers. These community organisers provide the community with access to someone to share and escalate their housing issues. Due to the time involved in community-led housing, this initiative is currently small, and it is likely that the impacts of this will not be felt in the Hyperlocal Booster Community Life Survey data for some time.

As noted elsewhere, the Empowering Places areas were purposely chosen because we knew that there were significant issues that needed addressing, many of which are systemic and were exacerbated by the pandemic and its aftermath. It is, therefore, not surprising to see these negative trends reflected in the data for Dyke House and other catalyst areas. Overall, it appears that the extent to which Empowering Places helps improve satisfaction with local spaces for those who haven’t been directly involved with the programme is mixed and not yet clear. However, there is strong evidence of the value of these services from those who engage with and use them.

4.2 | Community engagement and social action

Community businesses can use the assets and knowledge in the community to address issues that the community faces.43 It is hard to capture instances of how and where local empowerment and pride have improved. There is, however, evidence in the qualitative Empowering Places evaluation that local residents have started getting engaged in local decision making. For example, in Hartlepool, Wharton Trust staff described how local residents were beginning to identify challenges and needs, and approaching them with ideas about possible solutions and community businesses to help. The catalysts and community businesses have deliberately shaped services to empower local residents, which has a positive impact on those people involved. For example:

‘The catalyst facilitated people to come together to explore what would it mean to make that place a better place, the place where people want to live and thrive and grow and develop and be, a key role it plays is it’s not speaking on behalf of them, it’s not speaking for them.’ Stakeholder

A catalyst staff member at Wigan and Leigh Community Charity reflected that, since opening Platt Bridge Community Forum, residents had been coming with proposals to pick up and lead community activities independently, even taking on managing the community forum.

‘ ... people are running, you know, people taking action on it, and recognising it, and doing things and not being reliant upon other people, are reliant on themselves and with other people.’ Catalyst

The results from the Hyperlocal Booster Community Life Survey found limited observed differences between the Empowering Places areas and their matched comparison samples across specific measures of social action. The only statistically significant positive trend was in Braunstone, Leicester, where the proportion of residents reporting civic participation over the prior 12 months increased from 24.8% to 26.1% between 2018 and 2022. This was a 4.4pp relative increase relative to its comparison sample.

| Table 4.4: Proportion of residents reporting civic participation over the past 12 months | |||||||

| 2018 | 2020 | 2022 | DID | ||||

| CB | MCS | CB | MCS | CB | MCS | ||

| Braunstone, Leicester | 24.8% | 28.4% | 34.5% | 32.6% | 26.1% | 25.3% | 4.4% |

There were negative civic engagement trends elsewhere: a 2.3pp relative decrease in civic activism in the past year in Abram Ward, Wigan and 4.2pp decrease in civic consultation in Dyke House, Hartlepool.44

| Table 4.5: Proportion of residents reporting civic activism in the last 12 months | |||||||

| 2018 | 2020 | 2022 | DID | ||||

| CB | MCS | CB | MCS | CB | MCS | ||

| Abram Ward, Wigan | 6.7% | 4.8% | 3.7% | 5.3% | 4.3% | 4.6% | -2.3% |

| Table 4.6: Proportion of residents reporting civic consultation in the last 12 months | |||||||

| 2018 | 2020 | 2022 | DID | ||||

| CB | MCS | CB | MCS | CB | MCS | ||

| Dyke House, Hartlepool | 15.0% | 8.5% | 15.1% | 12.0% | 12.6% | 10.4% | -4.2% |