What we do

Community Climate Action

Community business at the heart of meaningful & inclusive climate action.

As the impacts of interconnected climate, energy, and cost-of-living crises increase on our society, the imperative for a fairer, greener future demands a transformative shift in our economy. While this transformation poses its challenges, it also presents an unprecedented opportunity to forge a new economy that prioritises people, planet, and communities above all else.

Community businesses are beacons of hope and crucial agents of change in combatting these crises together. Despite the barriers they face, these enterprises are already at the forefront of climate action, while simultaneously bolstering and building resilience in local economies and fostering improved social outcomes in their communities.

Community work IS Climate work

Our latest research with IPPR North and Locality scopes the role of community business in climate action, providing practical resources on viable climate action pathways.

Driving positive change

The latest case studies from community businesses all over the country taking action on climate.

Bradford Organic Communities Service

Providing organic fruit and veg, as well as recycled paint and crafts, to the people of Bradford.

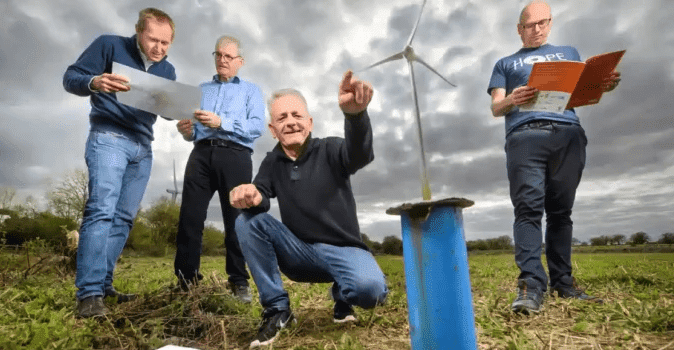

Ambition Community Energy

England’s largest community-owned wind turbine powering over 3,000 homes in Lawrence Weston.

Witton Lodge Community Organisation

Community anchor organisation in Birmingham that transformed derelict land into useable green space and turned the old park keepers cottage into an eco community facility, reducing energy costs by 55%

Fordhall Farm

England’s first community-owned, chemical-free farm in Shropshire. Educates on sustainable farming and supports local communities.

Pollenize

Pollenize uses the power of community and science to fight against pollinator decline.

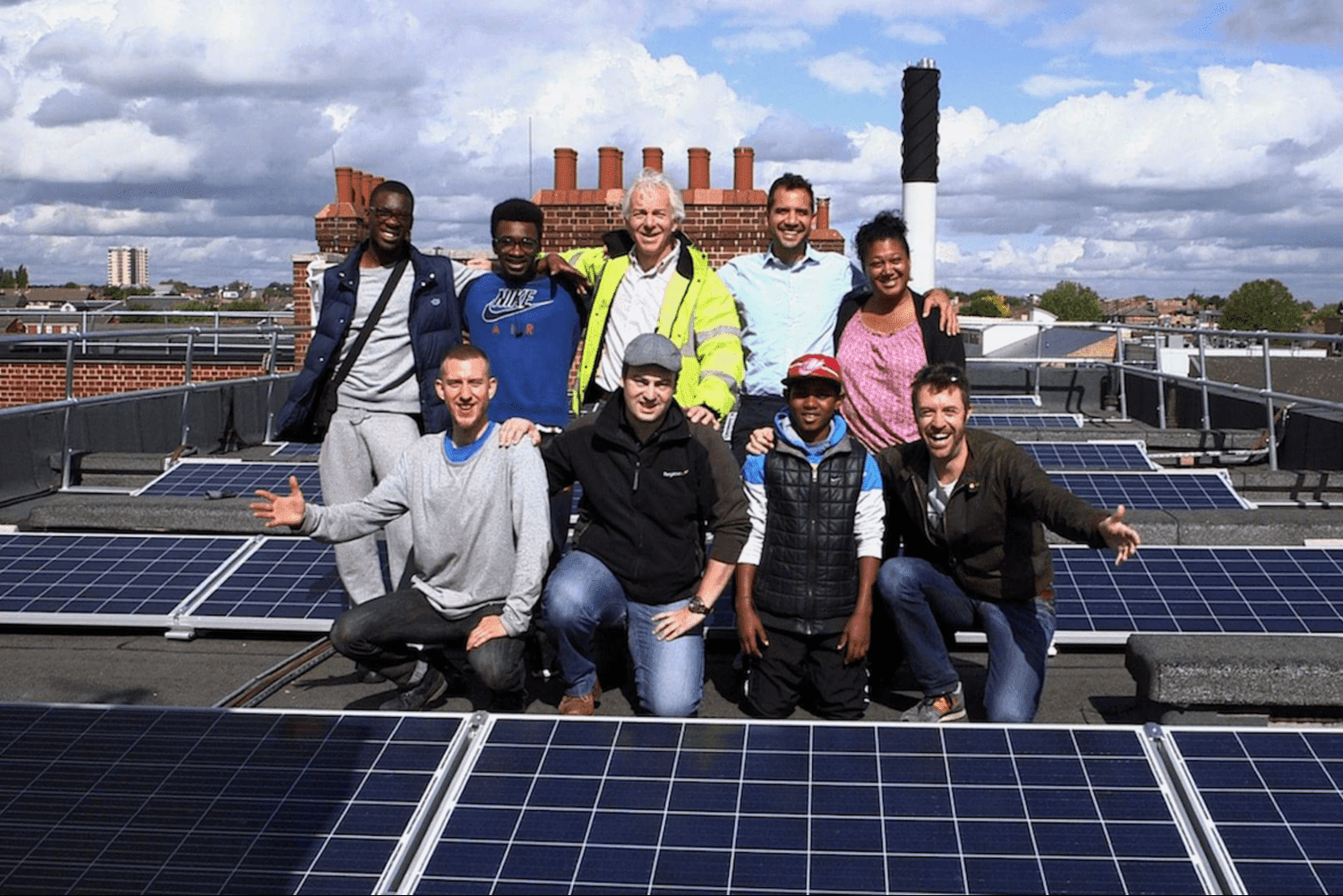

Banister House Solar

Residents of Banister House turned disillusion into the UK’s largest community-owned solar energy project on social housing.

Community Climate Action

In our latest blogs

Labour’s high streets plans a welcome step to Take Back the High Street

‘Growing across’ – why inclusive growth must be part of the industrial strategy

What next for the communities agenda?

“We believe that climate injustice goes hand in hand with social injustice, and that caring for the planet provides a huge opportunity to care for ourselves and our communities.”